Over the holidays, I found some time to work on a small idea I had for a while. As a sometimes-Google Workspace admin with a security background, I’ve always been aware of the risk of having public Google Groups. They’re an easy vector for the Ticket Trick attack, where email OTPs or verification emails are sent to a Google Group under an official company domain, allowing that user to then create or verify an account as <GOOGLE GROUP>@companya.com. Depending on how well the company has secured their account management controls, this can leak access to internal portals or SaaS tenants.

While writing this up, I realised this had already been done about six years ago, but I thought what was interesting was the evolution of the tooling and approach.

Workflow 🔗

In the previous researcher’s workflow, they chained EdOverflow’s googlegroups.sh script with a screenshot tool to figure out which Google Groups were public. However, with the advent of vibe-coding, I’ve found that “classic” tooling can be easily replaced with your own generated tools. This allows a lot more precision and customisation. In addition, I’ve found that a lot of open-source security tools tend to accumulate bloat and features over time, when there’s really no beating the simplicity of the Unix philosophy of “do one thing and do it well” and chaining many small tools with stdin and stdout.

For example, the original workflow only looked for a default overview group. I don’t think this is necessarily a default-open or automatically-created group anymore. It might make more sense to find other group names.

With that in mind, I had this workflow in mind:

- Fetch all Google Group URLs using passive sources such as AlienVault.

- Normalise, deduplicate, and filter them.

- Check these groups for public access (read/write).

I opted to go with a set of Golang programs for better native library support for web tasks - I really wanted a zero-dependency set of tools. You can check out the vibe-sec-tools repository I created here under google_groups_recon.

Vibe Coding Tips 🔗

Given the extremely simple nature of these modular tools, Claude could one-shot most of them, with a few tweaks here and there. For example, I needed to manually figure out the appropriate regexes and filtering criteria for “public” Google groups. Nevertheless, I’d recommend the Unix approach to vibe-coding sec tooling - keep it singular in purpose, break them up into modular components, with a simple stdin-stdout paradigm. It’s all about context / token management here.

Results 🔗

While I had high hopes, the drop-off rate was higher than I expected, likely because I was using a publicly-available source:

- 32k+ Raw URLs

- 1k+ deduplicated URLs

- 600+ unique domains

- 150+ publicly readable/writable Google Groups

While 150 might seem like a lot, most of them were spam or scam groups. In addition, while some allowed anyone to join the group, posting was limited to members only, preventing them from being abused as a ticket trick vector because the email OTP would be blocked. Finally, some groups also had spam filters or moderation on that further blocked simple Ticket Trick attacks.

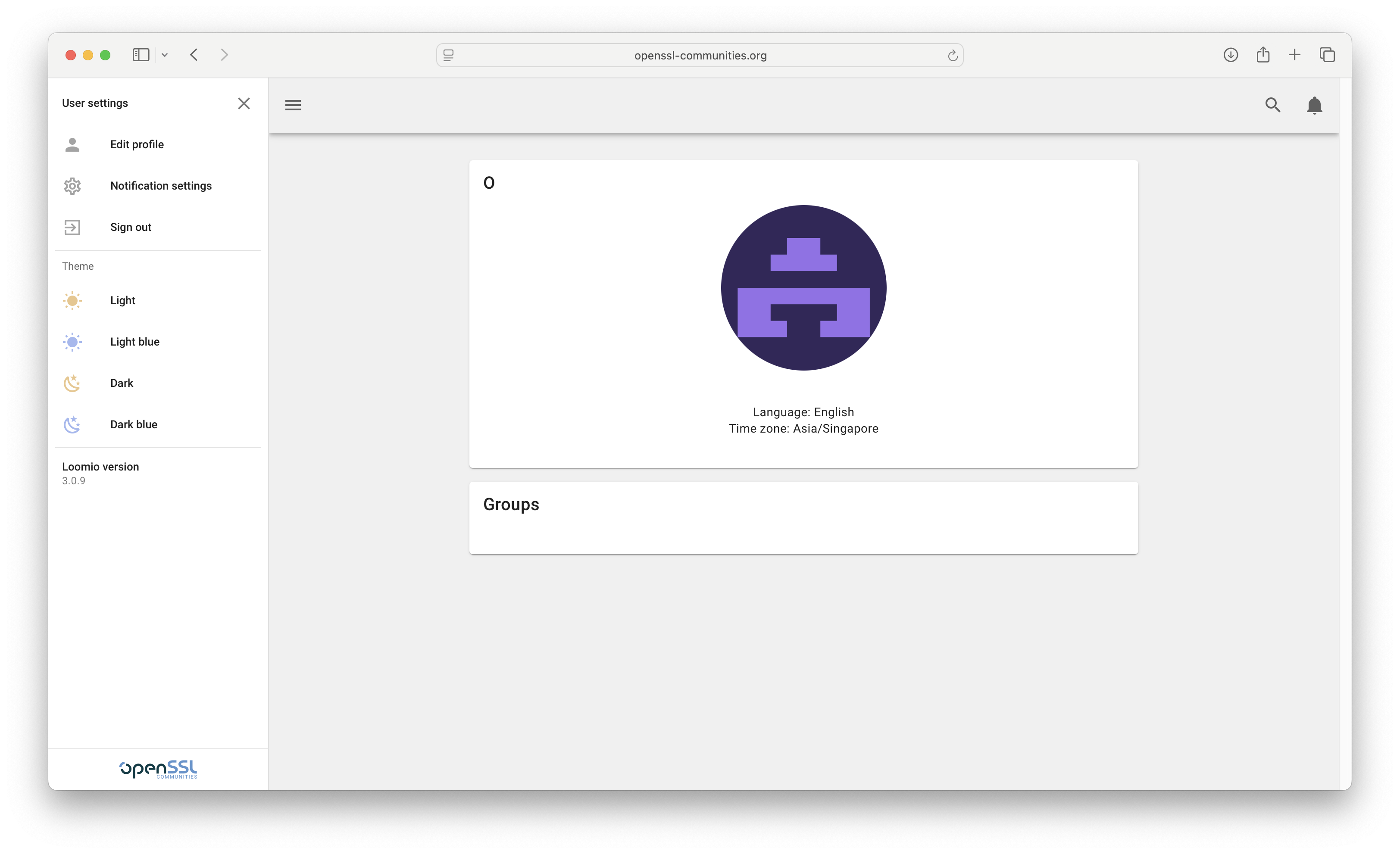

One of the vulnerable instances was an OpenSSL.org group, which I could then use to sign in as an official openssl.org email to their mail OTP community portal.

I quickly reported it and the team fixed the misconfiguration just as quickly.

While I didn’t venture much further, there are still some serious implications in a Ticket Trick attack even if many SaaSes (except Slack, here’s looking at you) have mostly patched some vulnerable-by-default configurations already. You could verify your emails on GitHub commits, auto-join SaaS tenants that whitelist entire domains, and other mischief. The bottom line is that any sane configuration should never rely on email as a souce of truth for identity, and instead use OIDC, SAML, and other established standards before granting access. Unfortunately, email OTP and magic links are often the past of least resistance and present a very attractive option for organisations that can’t be bothered/have no budget to set up better alternatives.

In any case, if you’re a Google Workspace admin or your organisation is using it, there’s really no reason to allow public groups (or external members) without a very good reason. The persistence of this issue six years later really shows how this is a footgun waiting to blow up. Hop over to the org-wide policies and set some sane defaults.